eUK ವಿಶೇಷ: Since time immemorial, to be precise, for the last 3000 years, the two animals have been used immensely in battles: elephants and horses. Usually, three major characteristics define the usability of animals in battles: size, weaponry, and controllability. Elephant’s size is intimidating, while its tusks, feet, trunk and forehead are formidable weapons. Elephants, despite being intelligent, are relatively tough to train, especially for battlefield purposes. Horses, though, do not have a dreadful size, but they allow humans to sit comfortably on their backs. They are easily controllable and trainable, but their main asset is their speed, capability of travelling long distances and maneuverability due to their inner strength. They could even travel 100 miles per day. Had these Central Asian horses not been so capable, India may still have been basking in its ancient glory.

In contrast, Indian horses were found to be relatively weak, mainly due to heat and humidity in India. On the other hand, Indian elephants were found to be of excellent quality, even better than their African counterparts. Elephants have a special place in Hindu Puranic tales. Hindu god Ganesh has the head of an elephant and the epics Ramayana and Mahabharata extensively portray elephant warfare. In ancient India, the army consisted of four significant parts: infantry, cavalry, elephants and chariots, collectively called chaturanga. Thus, the game of chaturanga came into being that later evolved into the game of chess, wherein the Elephant (rook) is considered a powerful piece.

Historically, kings and commanders used elephants for myriad works like cargo vehicles to carry heavy loads over long distances due to their sheer size. Kautilya stated that breaking fortress walls, gates and towers was among the elephants’ essential functions and further declared that the victory of kings in battles depended mainly upon elephants. Other Indian writers also expressed the utility of elephants in no uncertain terms: Where there are elephants, there is victory; the kingdoms depend on elephants. One rightly said that ‘one elephant, duly equipped and trained in the methods of war, is capable of slaying six thousand well-caparisoned horses’; or ‘an army without elephants is as despicable as a forest without a lion, a kingdom without a king or as valour unaided by weapons.

In Europe, they were only used as draught animals to carry weights. Babur once stated that his elephants could carry even 500 kgs of load. Two or three sturdy elephants could bear arms and ammunition, usually requiring 500 men. Elephants can walk up to 16 Kms/hr and can move in any terrain, whether on a steep slope or plains. They can even cross rivers with relative ease, which makes them ideal for war. Further, most carnivore animals like lions and tigers are fearful of elephants providing the riders a safety net. In Asia in general and in India in particular, they were used extensively as war tanks to be used to ramrod enemy flanks. On the flip side, they are also known to be voracious eaters.

To tame elephants, extensive training was required for years, during which they were trained to trample down the enemy and kill them mercilessly. They were also taught to endure large sounds to acclimatize them to war noises, or else they would panic in battle. Animals were deliberately slaughtered in front of them to make them accustomed to the sight of blood. An elephant is finally considered tame and trained when it allows a man to ride on its back.

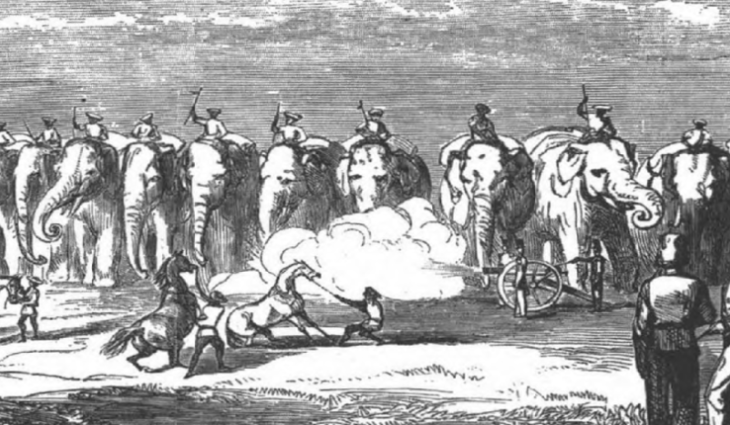

Elephants were integral to Hindu armies and used primarily for shock and awe. Hasan Nizami characterized the series of elephants as ‘mountains of steel’. These animals acted as command centres or a platform to throw javelins. Initially, Turk armies suffered heavy losses due to elephants. After a few initial reversals against Hindus, the Turks figured out myriad ways to neutralize elephants. They usually employed axes and arrows to hit the beast’s legs to hurt him, as its feet were susceptible. They also used to put caltrops or rods with spikes on the ground. They frequently used to cut its trunk with their sword, forcing it to run away from the battle. Turkish invaders used to throw burning naphtha (combustible oil) balls at the rushing elephants, thus harming them immensely. Mahmud used this technique to defeat Hindu Shahi king Anandpal when the Turks were on the verge of defeat. Afterwards, it became a standard operating procedure, to be used against marauding elephants. It significantly reduced the importance of elephants in wars. However, Hindus kept using them in the battles, even though they were more of a liability, given their slow mobility.

These animals were most useful with the enemies that had not fought against them earlier as happened with Ghori in the first battle of Tarain in 1191. Realising his mistake, Ghori reportedly practiced with dummy wooden elephants before attacking again in 1192. After the advent of gunpowder in the 16th century, the practical utility of this large but unpredictable pachyderm was reduced largely. Probably they were given up in favour of artificial and predictable weapons.

On the contrary, the Turks’ biggest strength was their large Turkoman horses. These horses required large arid tracts of grasslands that were not present in the cultivated plains of India with its humid climate. Even if the battles were lost, they could retreat safely at a fast speed due to their sturdy horses to prepare for the next conquest. With their weak Indian horses, Hindu armies could not chase them down. Even when Hindu kings wanted to finish the invader’s army, they could not. The Turkoman horse is the noblest in the whole of Central Asia and surpasses all other breeds in speed, endurance, intelligence, faithfulness and has a marvelous sense of locality. On their predatory expeditions, the Turkomans often covered 650 miles in the waterless desert in five days. They owed their power to the training of thousands of years in the endless steppes and deserts and to the continual plundering raids, which demanded the utmost endurance and privation of which horse and rider were capable. This swift mobility enabled the commanders to send soldiers on advanced reconnaissance and spying missions. The transmission of messages between Bin Qasim and the Caliph of Basra during the attack on Sindh was quick due to this characteristic. Ghazni could launch 17 attacks on India in just 25 years also points to this extraordinary mobility.

Due to their rigorous training, they developed into outstanding horse archers. They could aim and accurately shoot six arrows per minute. The effective range of the composite bow used to be 300 yards and a maximum of 500 yards. This ability could destroy sword-wielding Armenians from a distance from the Turk archers. Further, the latter’s bows were composite ones made of wood, horn and sinew. The strings were of animal hides that made them stronger. The main advantage of these bows was their higher power and smaller size. They also used nawaks (crossbows), arrows that easily pierced the enemy’s armour. Bows were accorded sacred status along with the horses. Turks also used metallic stirrups to deploy heavy cavalry on the battlefields, while Hindus used rudimentary stirrups made of wood.

Until the 12th century, Rajputs used to import 10,000 horses from Central Asia. However, Turks and Mongols later stopped exporting horses, fearing that the animals would be used against them only. After coming to India, most horses used to fall sick due to heat, improper feeding, and lack of horseshoes. Later on, crossbreeding was tried between Arabian and Indian horses so that the hybrid could survive in India’s humid weather. Famous Marwari horses were the output of this process only; still, they were no match for the Turkish horses. Its hilly and forested terrain was not suited for horses at all. Conversely, this terrain was perfect for the elephants and hence Indian rulers came to rely upon the elephants.

The combined factors of the continued use of elephants and the absence of sturdy horses contributed heavily in keeping Hindus under Islamic rule for 500 years.

ಕೃಪೆ: http://bharatvoice.in